Why British Hunters Overheat: Layering Mistakes Most People Don’t Realise They Make

Learn why British hunters overheat and how to fix it. Discover layering mistakes, moisture issues, and cooling methods for safer, more successful hunts.

If you spend enough time hunting in Britain, you start to notice a pattern. The weather rarely settles on one mood, the ground stays damp long after the sky clears, and the clothing that once kept you alive in winter suddenly becomes a furnace by early season. Hunters talk about cold fingers, wet boots, and sleet stinging the face, but there’s another issue that rarely gets named out loud: overheating. Not the dramatic, collapsing-on-the-trail sort, but the quiet, creeping heat that builds under the wrong layers until you’re forced to slow down, strip off mid-stalk or, in the worst cases, simply abandon hunts because the discomfort becomes too much.

It happens more often than anyone likes to admit. A hunter sets off warm, almost smug, with what feels like sensible layers. Within minutes, the body temperature climbs, moisture starts clinging to the base layer, and that first wave of trapped warmth becomes unmistakable. The air might feel cool on the hill, but inside your jacket, you’re running a different climate entirely: one shaped by movement, effort, and how well (or poorly) your clothing manages body heat.

Britain doesn’t have the dangerous desert temperatures that make headlines, yet hunters here are surprisingly prone to heat exhaustion and even heat stroke, largely because conditions are misleading. Cool wind. Patchy sunshine. A sky that promises rain. These elements invite people to overdress, and the results often go unnoticed until vision blurs, breathing quickens, and everything begins to feel, quite suddenly, wrong.

The same problem affects hunting dogs. They work low to the ground, close to scent, wrapped in their own fur, and driven by instinct rather than logic. They don’t consider whether they’ll easily overheat; they just run. And by the time the glassy-eyed look appears, by the time the tongue hangs wide and flat, spotting the signs can feel like a race you wish you hadn’t entered.

This guide aims to show why British hunters, and working dogs, run hotter than they realise, and how a better layering system, proper moisture management, and a little knowledge about temperature can make every outing safer, calmer, and far more successful.

Overheating While Hunting: The Hidden Risk Most Hunters Ignore

Few hunters imagine themselves overheating in Britain. It feels like a problem for warmer places, the sort of thing that happens in an open desert, not under grey skies. Yet overheating while hunting happens precisely because hunters overcompensate for cold starts. Mornings begin chilly; you dress for the chill. Twenty minutes later, effort kicks in, your internal furnace wakes up, and suddenly you’re sweating into fabrics that were never designed to handle that much moisture.

The trouble with sweat is simple: when it can’t escape, it turns into a warm fog around your torso. Waterproof jackets and over-insulated midlayers trap heat, pushing the body temperature beyond what feels comfortable. Hunters can reach dangerous levels without realising, the brain focuses on the task ahead, not on the creeping warmth underneath.

When heat builds for an extended period, coordination dulls, breathing shifts toward extreme hyperventilation, and the decision-making that once felt sharp becomes strangely sluggish. On humid days, especially in woodland or valley cover, the air feels thicker, and the risk of heat stress climbs faster than most expect. Even efficient hunters become inefficient hunters when energy drains into managing the heat instead of managing the hunt.

Body Temperature: What’s “Normal” During Hunts?

A resting human maintains a normal body temperature around 37°C, but a hunter in motion rarely stays there. With a rucksack on your back, rifle in hand, and boots biting into soaked ground, every movement produces body heat. The air around you might feel cool, but inside your clothing system, you’re edging closer to warm, then hot.

British hunters often swing between cold at the start of a session and uncomfortably warm within minutes, especially on hillsides where the ambient temperature shifts with altitude. Add sunshine breaking through clouds, a rise in pace, or a quick climb out of a gully, and the temperature can skyrocket.

When the temperature rises too far, the body attempts to cool itself through sweat glands. That’s perfectly normal until sweat becomes trapped by poorly chosen layers. Then you’re not cooling; you’re soaking. And soaking under insulated layers doesn’t just feel unpleasant. It risks dangerous drops in body temperature later, once you slow down.

Body Heat: Why British Hunters Retain Too Much Warmth?

One reason British hunters overheat is that we’re taught to stay warm first and avoid the cold at all costs. But overdoing warmth often means you retain body heat far more than you need. When your base layer is cotton, when your midlayer is too thick, or your shell lacks venting, you essentially create a sauna inside your clothing.

Moisture is the real culprit here. Once moisture soaks into layers and warms up, that heat sits close to the body, unable to escape. You become your own radiator, slowly cooking inside your gear even when the weather feels manageable.

Hunters often step out dressed for a full winter storm when the elements only call for light protection. This mismatch creates a trap: the body generates heat, but the clothing refuses to release it. The result is predictable and uncomfortable: overheating, sweating, then chilling once activity slows.

Hunting Dogs: Why Working Dogs Easily Overheat Too?

If humans overheat easily, hunting dogs are at even greater risk. Their anatomy works differently: a wide tongue for evaporative cooling, ears that release heat, and a habit of lying flat to cool the belly. But none of that helps when the dog is working scent in thick cover.

A dog at low activity stays steady, but once the drive kicks in, their body heat multiplies rapidly. And unlike us, dogs don’t downshift when they feel hot; they push on, focused entirely on the task. On warm summer days or during an early-season session, a dog can drift from warm to dangerously hot with little warning.

Symptoms creep in quietly: that glassy-eyed stare, slowing steps, heavy panting, the urge to stand still for longer and longer periods. In the worst cases, vomiting appears, followed by collapse. A handler must watch for these signs constantly, especially near standing water, ponds, or a shaded kennel, where heat might briefly relent.

It doesn’t help that certain breeds, those descended from fast coursing animals like the cheetah or leopard, generate heat quickly during bursts of speed. Their physiology is designed for rapid acceleration, not for maintaining a safe temperature during long hunts.

To prevent overheating, handlers use simple, effective interventions: offering cool water, allowing small drink breaks, providing a splash in shallow water, or applying ice to the belly, armpits, or head. In emergencies, some handlers use rubbing alcohol on paw pads to promote evaporation before contacting a vet.

Outer Layer Mistakes: When Clothing Traps More Heat Than It Releases

The outer layer is often the villain in overheating stories. British hunters love heavy jackets: thick, protective, weatherproof, reassuring. But these jackets aren’t always built for movement. They excel at stopping wind and rain, yet they lock in heat the moment you push uphill.

When an outer layer prevents air flow, it shuts down the body’s natural cooling mechanisms. The hunter ends up hot, soaked in sweat, then oddly chilled once they rest. A good jacket should let you stay comfortable across changing pace, not just stay warm during low movement.

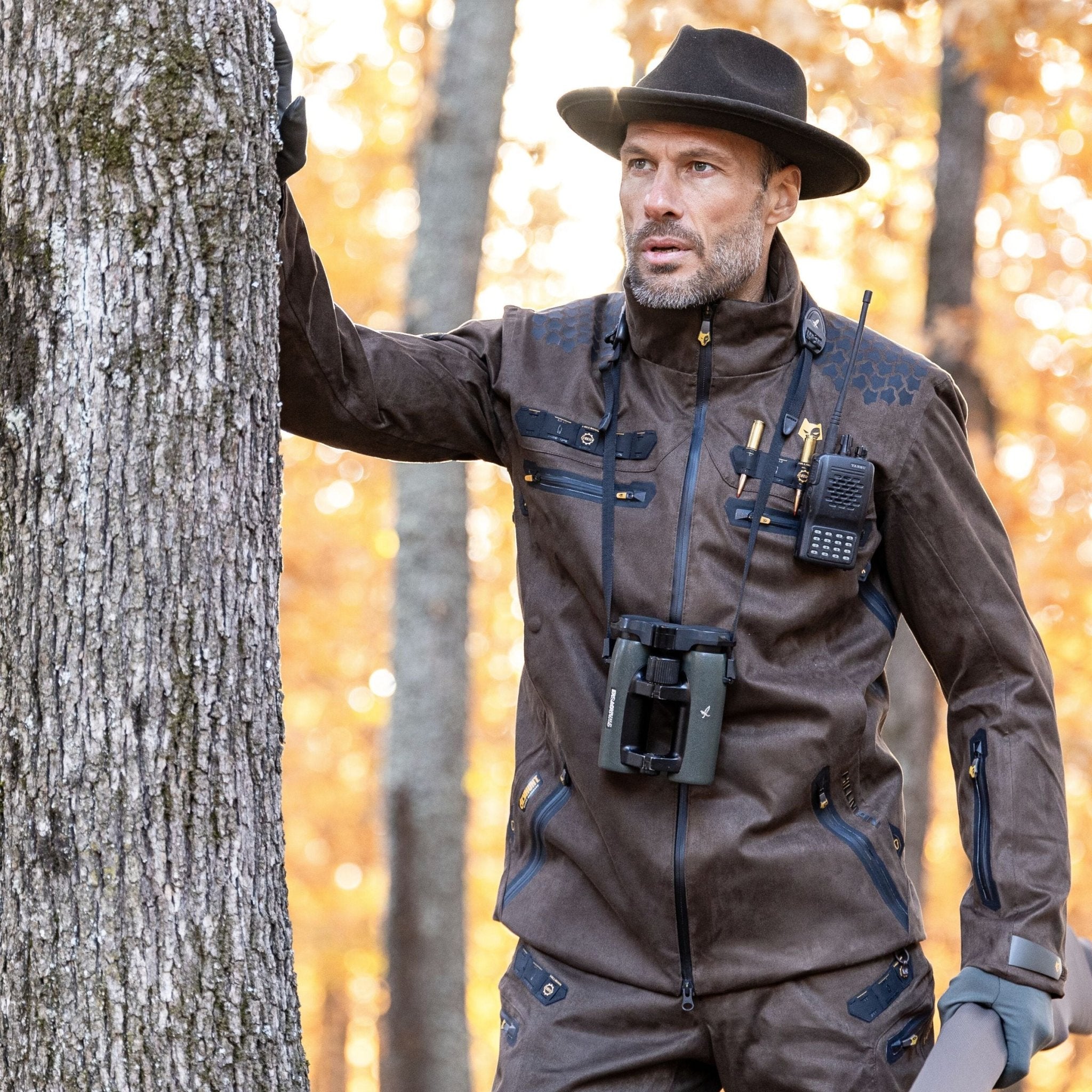

A proper layering method prevents this. Hunters who understand how to combine base layers, midlayers, and shells rarely struggle with overheating. Those who don’t often feel trapped, as if the jacket refuses to cooperate with their rhythm.

Heat Stress in British Weather: Why Your Gear Makes It Worse?

Heat stress emerges when the body can no longer regulate its temperature: a state that arrives shockingly fast when layers aren’t breathable, or the pace is too high. Even mild humidity in woodland contributes, creating an invisible barrier that stops sweat from evaporating.

Some scientific studies, including work published in Biology Letters, show that mammals under intense effort generate heat faster than the environment can offset. Hunters are no exception. If clothing prevents heat release, the work becomes harder, breathing becomes shallow, and the risk of heat exhaustion rises.

Left unchecked, heat exhaustion can become heat stroke, which is life-threatening. Confusion, dizziness, nausea, and changes in head sensation, none should not be ignored. The course of heat injury is rapid, and knowing when to pause, cool down, or retreat is part of responsible hunting.

Layering System Problems: How Most Hunters Get Layers Wrong?

The layering system exists to adjust warmth as the environment changes, but many hunters misunderstand how it truly works. They pile on layers expecting insulation, only to find themselves roasting under too much protection.

Cotton base layers absorb moisture instantly, trapping heat. Heavy midlayers worn during active stalks force the body into overdrive. Shell jackets zipped tight at all times prevent excess heat from escaping. Each mistake adds up until the entire system becomes a heat trap.

The key lies in using layers to drop heat when needed, not only to hold it. Choose fabrics that wick moisture, venting areas near the underarms or back, and materials that respond to movement rather than suffocating it.

Moisture Management: Why Sweat Is Your Real Enemy?

Effective moisture management is what separates comfortable hunters from miserable ones. Sweat is the body’s cooling method, unless clothing blocks evaporation. Once trapped, sweat quickly warms, creating a humid environment that pushes you into overheating territory.

When sweat cools suddenly, usually during rest, hunters become chilled even on mild days. That’s why breathable base layers, venting options, and light fabrics matter. Without them, you’re either too warm or too cold, never balanced.

Abandon Hunts: When Heat Forces You to Stop?

It’s rare for hunters to admit they must abandon hunts due to heat, but it happens more than you’d expect. The body can handle cold far better than prolonged heat, and once your core overheats, focus evaporates.

Poor performance, slow reactions, foggy thinking, and diminishing strength make the hunt not only unpleasant but unsafe. No successful hunts come from pushing past physiological limits.

Successful Hunts: Staying Cool Enough to Perform Well

A comfortable hunter is an efficient hunter. Managing heat, choosing smart layers, and using cool water, shade, and airflow at the right moments all contribute to a smoother day.

Small methods, like carrying a bottle of water, pacing yourself, or removing a midlayer before exertion, help maintain performance during hunting sessions. Protect yourself from the sun, observe your body, and use smart protection against both warm and cold conditions.

Working Dogs: Cooling Methods Every Handler Should Know

Cooling a dog isn’t optional; it’s part of fieldcraft. Letting a dog wade briefly in standing water, providing a shaded truck, or giving small amounts of cool water can make the difference between a healthy working day and a dangerous one.

If symptoms worsen, like wobbling, vomiting, collapsing, or the dog trying to stand still indefinitely, it’s time to apply ice, use the evaporative cooling method, or contact a vet.

Stay Warm but Not Hot: A Balanced Layering Method for British Hunts

The aim is simple: stay warm without roasting. A clever system uses fewer, lighter layers, each handling moisture well and releasing excess heat. The body stays dry, the mind stays clear, and the hunt becomes a pleasure rather than a test.

Understanding Heat, Layers, and the Biology of Overheating

British hunts aren’t defined only by cold winds and rain. Heat plays its part too, often quietly. Understanding how the body, clothing, and environment interact lets you move smarter, protect your life, and keep yourself and your dog safe under shifting skies.

FAQ

Why do hunters overheat even in cool British weather?

Because effort raises your body temperature far faster than you feel it. The air may be cool, but layers that trap body heat build warmth quickly, especially during uphill stalks or when the outer layer doesn’t breathe well enough.

What are the early signs of heat exhaustion while hunting?

Slowing down for no clear reason, feeling strangely foggy, heavy breathing, a hot face, and damp base layers. If the vision sharpens oddly or you feel glassy-eyed, you’re already pushing it.

How can I stop overheating under a waterproof jacket?

Open vents early, not once you’re already sweating. Use light layers and fabrics with good moisture management. Remove insulation before effort, not after. Waterproof gear is brilliant for rain, but it can make you far too warm if you overdress underneath.

What should I do if my hunting dog shows signs of overheating?

Move the dog into shade, give cool water in small amounts, wet the belly and ears, or apply ice if needed. If wobbling, vomiting, or collapse start, contact a vet immediately: dogs can go from warm to dangerously hot fast.

How many layers should I wear to avoid overheating?

Fewer than you think. One moisture-wicking base, a mid-layer you can remove quickly, and an outer layer that releases excess heat usually works for most British days. The goal is flexibility, not insulation at all costs.

Share:

How to Stay Dry on a British Hunt: Rain, Wind, and Damp